Onboarding, integration, welcome courses... The subject is now rooted in the HR strategies of companies. Dedicated tools, checklists, digital programs: on paper, organizations have never invested so much to ensure the arrival of their new employees. But as soon as you leave the headquarters to observe the reality on the ground, the picture becomes more complex.

By field teams, we mean all employees whose work is carried out mainly outside offices: store sales teams, maintenance technicians, industrial operators, logistics agents, caregivers, itinerant salespeople or even employees present on construction sites. Essential jobs where structured onboarding becomes a real challenge.

Geographical distance, staggered schedules, limited access to digital tools, managers absorbed in operational matters: field integration combines specific constraints that make conventional devices difficult to use. However, an approximate onboarding process directly affects service quality, security, customer experience, and retention rates. The onboarding of field teams is not a simple logistical solution: It is a strategic issue in its own right.

Why traditional onboarding systems fail in the field

If the onboarding of field teams poses so many difficulties, it is not because of a lack of effort or goodwill. This is because the majority of the programs were designed for work environments that have little in common with the reality on the ground.

So-called “classical” onboarding processes are implicitly based on several conditions: dedicated time, employees available at the same time, easy access to information, and a clear separation between working time and learning time. However, these conditions are rarely met on the ground. The activity does not stop, the teams rarely meet, and operational urgency almost always comes first.

Faced with this, a belief persists, often unconscious: in the field, we learn naturally by observing and doing. It would be enough to look at an experienced colleague, to repeat the actions, and learning would follow. In reality, this method quickly shows its limits. Observing is not understanding, repeating is not mastering, and doing without structured feedback leads to reproducing approximations.

It's a bit like learning to play guitar by watching a concert from the pit. You can see the fingers moving, but without explanation or feedback, it's difficult to replay the song once at home.

Another pitfall is the way in which information is transmitted. Due to lack of time, we concentrate the essentials at the very beginning: rules, procedures, safety instructions, managerial expectations. The newcomer receives a lot, very quickly, but without being able to relate this information to concrete situations. Learning then remains superficial, fragile, and difficult to transfer to the workplace.

Informing is not enough: the main pitfall of field onboarding

When field onboarding does not work, the reflex is often the same: add content. One more procedure, an explanatory video, an additional e-learning module. As if the problem was due to a lack of information.

In the field, this is rarely the case. Newcomers usually get a lot of stuff in the first few days, often way too much. Internal rules, safety instructions, tools, goals, goals, values, corporate culture: everything is condensed at the beginning, in a very short period of time. The message is clear, but that is not the problem. Being exposed to information does not mean having understood it or being able to use it in a real situation.

Informing is not learning. Informing is the transmission of content. Learning involves actively dealing with this content, relating it to concrete situations, experiencing it, and then receiving feedback. In the field, this stage is too often absent. The employee listens, observes, then quickly finds himself alone in the face of operational reality.

Added to this is cognitive overload. By wanting to say everything too quickly, we undermine learning and skills development. The new employee retains a few elements, forgets the rest, and compensates as best he can, by imitating his colleagues or by improvising.

Moreover, another frequent drift is observed. For the sake of completeness, we try to tell everyone everything. However, not all employees need the same level of information at the same time. A salesperson in the field does not need to master all of the company's legal documents from the first week, whereas a lawyer cannot do without them. By dint of wanting to be complete, we often end up diluting the essentials and compromising the expected productivity..

Successful field onboarding: designing a progressive learning path

If informing is not enough, the question becomes obvious: what does field onboarding look like that really works? The answer is in one word: progress.

In the field, you don't learn everything at once. The situations are varied, the constraints are strong, and taking up a position is often under pressure. An effective onboarding process takes time, from the first days to the first weeks, and even the first months.

Concretely, this means thinking of onboarding as a structured employee journey, and not as a simple onboarding sequence. The first few days should allow the new talent to master the essentials in order to act without getting into difficulty. Only then come the subtleties, the more complex cases, the less frequent situations. The aim is not immediate comprehensiveness, but gradual autonomy.

This approach is based directly on principles from cognitive science. For example, you learn better when learning is spaced out, when you are led to act rather than listen passively, and when you receive regular feedback on what you do. But applying these principles in a field onboarding program requires real pedagogical work. However, not everyone is an educational engineer, and it is neither realistic nor desirable to expect managers or business experts to become one.

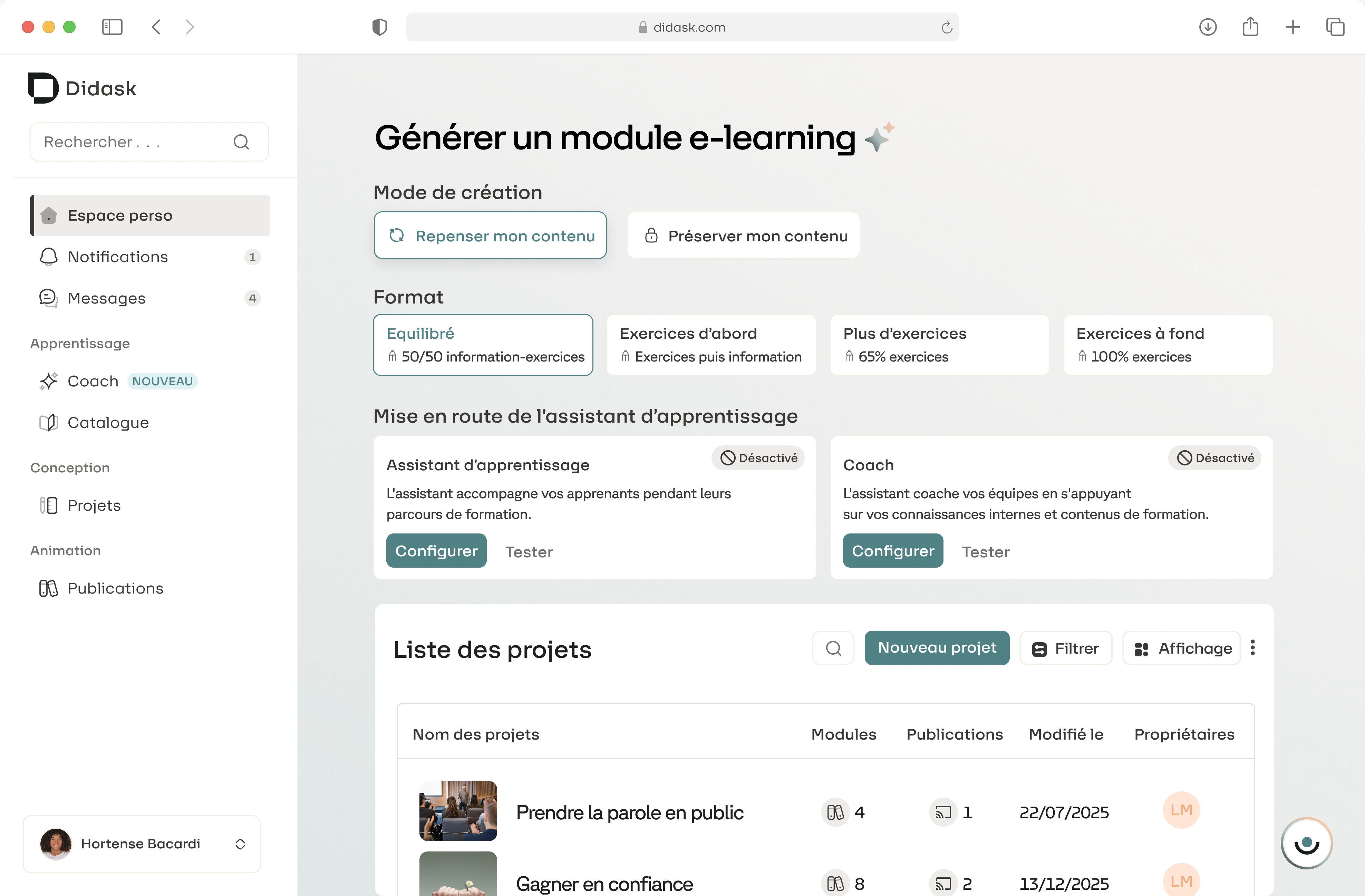

This is where the tools come into their own. Their role is not to add a layer of complexity, but rather to absorb it. Well-designed tools like Didask's make it possible to structure content, guide course planning and offer situations relevant, without requiring advanced pedagogical expertise. They make high-quality onboarding possible on the ground, but simple to deploy in real life on the ground.

Learning to do things remotely: a necessity for field integration

At this point, an objection often comes up. If field onboarding should make it possible to learn how to make decisions taken in a situation and principles from cognitive sciences, using technical gestures, then face-to-face training seems essential. In essence, the idea is well-defended. In the field, it is rarely sustainable.

Systematically training dispersed teams in person, with constrained schedules and sometimes high turnover, is simply unrealistic. Remote onboarding is therefore not a comfort option or an ideological choice, it is an operational necessity. The real question is not whether to train online or not, but how to do it without giving up the educational requirements posed earlier.

Because putting content online is not enough. For an online onboarding tool to really work in field jobs, it must check a few key conditions. One online training platform as Didask meets these requirements:

- It offers short formats, accessible quickly, compatible with the pace of the field.

- The contents are directly linked to concrete work situations, and not to decontextualized theoretical cases.

- The learner can practice, make choices, make mistakes, and receive feedback, rather than passively consuming information.

- Access comes at the right time, when the need arises, not just on the first day.

- Finally, the solution integrates into daily work tools (internal messaging such as Slack or Teams, CRM, business tools), without adding friction or taking the employee out of their workflow.

Learning to do at a distance is a bit like rehearsing a piece before a concert. Watching a live stream or reading a tablature is not enough. What makes the difference are the targeted rehearsals, the passages reworked, the mistakes corrected before going on stage. Digital technology can play this role of virtual mentoring, provided it is thought of as a training space, not as a simple content showcase.

Used in this way, remote onboarding becomes an extension of the field. It makes it possible to prepare an action before carrying it out, to secure an initial position, or to return to a poorly understood situation. In other words, learning to do things online is possible for field teams, provided they choose tools designed for action and practical implementation.

Managers and peers: key business experts to build field onboarding

For a field training, managers and peers are not only support relays. Above all, they are experts in real work. They know what you really need to know to be operational, what actions are critical, what mistakes are common, and what situations are the most difficult for newcomers.

As such, the manager's role in onboarding should not be limited to welcoming or answering questions. Managers and peers are in the best position to contribute to the very design of the integration path, by identifying the key skills to acquire, the situations to be worked on as a priority and the good reflexes to be transmitted. In other words, effective field onboarding cannot be designed only from a headquarters or an HR function: it must be rooted in business expertise and promote collective intelligence.

The problem is that these managers and peers are neither trainers nor educational engineers, and they are not destined to become one. Asking them to produce complex modules or to master advanced teaching concepts is unrealistic, especially in contexts of high operational pressure and daily talent management. Without appropriate tools, their contribution often remains informal, oral, and difficult to capitalize on in a group dynamic.

This is precisely where tools take on a new dimension. Their role is not only to disseminate content, but to allow field experts to easily transform their knowledge into structured learning. Tools capable of guiding the design, of proposing relevant scenarios and of automatically integrating the principles from cognitive sciences, while ensuring the educational quality produced for HR teams.

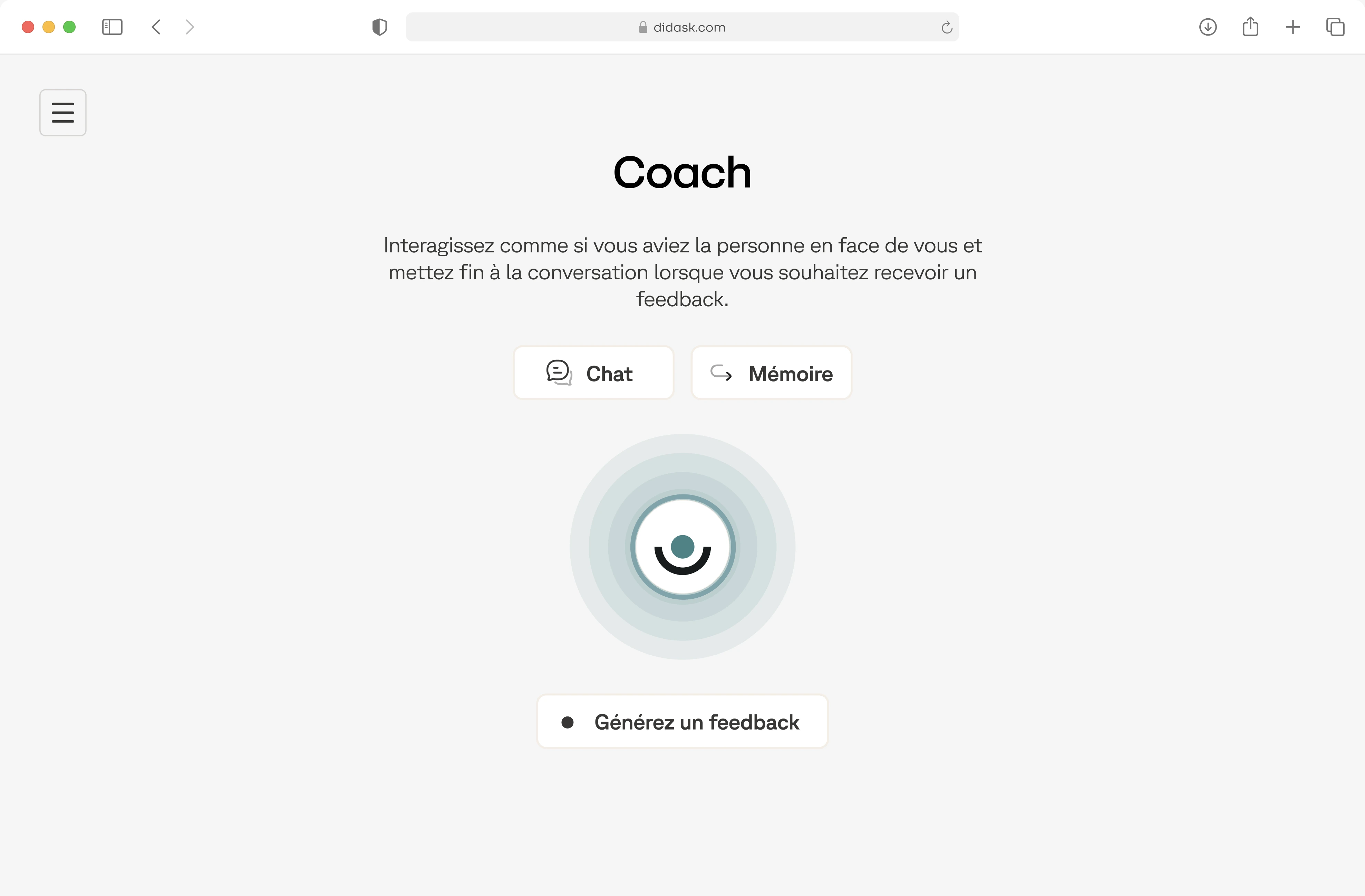

For example, this is what Didask allows with its educational artificial intelligence. Based on business knowledge, a document or field experience, the platform helps to quickly create effective training modules, without requiring specific teaching skills. Managers and experts can thus contribute to onboarding where they are most legitimate, on the content and meaning of the work, while the tool takes care of the educational complexity and facilitates internal communication.

Conclusion: measure, adjust and make field onboarding a sustainable lever

Successful field onboarding is not only judged by the end of the first week, nor by the number of content consumed. What really matters is what happens after that. Is the employee able to act alone in key situations? Does it make fewer mistakes? Is he gaining confidence? Does he feel legitimate in his role? The regular evaluation of these indicators makes it possible to measure the real return on investment of the program.

The challenge is not to measure everything, but to know how to adjust. A field onboarding process must evolve over the course of feedback, errors observed, and poorly controlled situations. Each new hire becomes a learning resource to improve the next journey and strengthen the organization's employer brand.

Ultimately, successfully integrating new field employees means accepting a simple reality: these jobs can be learned by doing, but never without a framework. They require progressive courses, tools capable of absorbing educational complexity, and the involvement of business experts where their value is maximum. It is precisely this combination between learning, connection with the field and technology that platforms like Didask make possible today.

The strategic onboarding of field teams is therefore not just about a good welcome or a well-intentioned career. It is a strategic lever for securing skills, improving the retention rate, encouraging commitment and making each arrival a real starting point for the development of sustainable skills.

.png)