How do we learn? This question has spanned centuries and shaped the evolution of our education systems. Today, in companies, vocational training faces a crucial challenge: to effectively support employees in a world that is rapidly changing.

Learning models offer scientifically validated answers to this fundamental question. From behaviorism to connectivism, each theory sheds unique light on the mechanisms that make it possible to move from information to competence. Understanding these models means giving yourself the means to design courses that really work.

This article explores the five main learning models recognized by cognitive science research. You will discover their principles, their concrete applications in vocational training and how to combine them intelligently to maximize the impact of your learning systems.

What is a learning model?

A learning model is a theoretical framework that explains how individuals acquire, retain, and mobilize new knowledge or skills. These models are based on decades of research in experimental psychology and cognitive science.

Contrary to personal intuitions or opinions, these theories are based on rigorous empirical studies. They systematically compare different teaching methods to identify which ones generate the best learning performance.

Why these models are essential for corporate training

In the professional context, choosing the right pedagogical approach directly determines the return on investment of your training courses. An inadequate model results in employees consuming content without developing real skills.

Learning models make it possible to answer concrete questions: should practice or theory be preferred? How do you deal with the error? What role should social interactions play during training? These educational choices have a measurable impact on the effectiveness of skills development.

A historical evolution that reflects our understanding of the brain

The history of learning models follows the evolution of our understanding of cognitive mechanisms. From the behaviorism of the 1900s, which saw learning as a black box, to the connectivism of the 21st century, which integrates digital networks, each model has enriched our vision.

This progression does not invalidate previous models. On the contrary, each theory maintains its relevance for certain types of educational goals. The real challenge is knowing when and how to mobilize each approach.

Behaviorism: learning through conditioning

Behaviorism marked the birth of the scientific approach to learning at the beginning of the 20th century. This model considers that learning occurs through observable changes in behavior, regardless of what is happening in the learner's mind.

For behaviorists, learning is about creating associations between stimuli and responses. This vision is based on the idea that the brain works like a black box: only inputs and outputs matter, not internal mental processes.

Scientific foundations: from Pavlov to Skinner

Ivan Pavlov is laying the groundwork with his experiments on classical conditioning. By systematically combining a neutral stimulus (a bell) with an unconditional stimulus (food), it shows that a dog learns to salivate at the simple sound of the bell.

John Watson then theorizes behaviorism by claiming that only observable behaviors should be studied. Burrhus Frederic Skinner goes further with operant conditioning: learning results from the consequences of a behavior (reward or punishment).

The principle of positive reinforcement is becoming central. When a behavior is followed by a pleasant consequence, it has a tendency to happen again. Conversely, punishment decreases the likelihood of the behavior being repeated.

Practical applications in vocational training

In the business world, behaviorism is particularly illustrated in the acquisition of automation. Safety procedures, quality protocols or repetitive technical actions benefit from this structured approach.

The method is based on breaking down complex skills into basic sub-tasks. Each microlearning is the subject of repeated exercises until complete automation. Immediate feedback (correct/incorrect) progressively reinforces good behaviors.

Corporate gamification systems also exploit these principles. Points, badges, and awards function as positive reinforcements to encourage engagement in learning paths.

The limits recognized by research

The main pitfall of behaviorism lies in the fragmentation of learning. By breaking down goals excessively, learners lose the big picture and struggle to transfer their skills into new situations.

This approach also neglects complex mental processes such as comprehension, reasoning, or problem solving. The learner becomes passive, reacting mechanically to stimuli without developing critical thinking.

Finally, behaviorism does not take into account the learner's prior mental representations. However, research shows that these initial designs massively influence the ability to integrate new information.

The Didask approach: integrating behaviorism wisely

At Didask, packaging finds its place in the creation of sustainable automation. Our training platform integrates spacing and repetition mechanisms to anchor good practices in long-term memory.

However, we go beyond simple stimulus-response by combining these principles with more elaborate cognitive approaches. The objective: to develop not only behaviors, but also a genuine understanding of the underlying concepts.

Cognitivism: understanding mental mechanisms

Cognitivism emerged in the years 1950-1960 as a reaction to the limits of behaviorism. This cognitive revolution coincides with the appearance of the first computers, offering a new metaphor: the brain as an information processor.

Unlike behaviorism, cognitivism is concerned with internal mental processes. Learning no longer consists in simply modifying observable behavior, but in transforming the cognitive structures of the individual.

Information processing: a thinking brain

Cognitive researchers like Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin model memory as a multi-step processing system. Information first passes through sensory memory, then through working memory, before potentially being stored in long-term memory.

This vision is radically transforming pedagogy. The challenge is no longer to condition responses, but to optimize the cognitive processing of information. Cognitive load is becoming a central concept: too much simultaneous information saturates working memory and prevents learning.

Donald Hebb shows that neural connections are strengthened with use. The more information a learner mobilizes, the more it is firmly anchored in long-term memory. This principle scientifically justifies the importance of repeated and spaced practice.

Cognitive strategies for learning

Cognitivism highlights the existence of effective mental strategies. Successful learners don't just passively receive information: they organize it, connect it to their existing knowledge, and create structured mental patterns.

Developmental learning is about enriching information by creating connections with what you already know. The hierarchical organization of knowledge facilitates its subsequent retrieval. Metacognition (thinking about one's own learning processes) is becoming a powerful driver of progress.

David Ausubel introduces the concept of meaningful learning. New knowledge is only sustainably integrated if it connects to the learner's pre-existing cognitive structures. Hence the importance of identifying the prerequisites and creating explicit bridges.

Practical business applications

In professional training, cognitivism inspires educational practices that focus on deep understanding. Designers structure information in a hierarchical manner, from the general to the particular, to facilitate the construction of coherent mental diagrams.

The use of visual representations (diagrams, diagrams, concept maps) uses the principle of double coding.

Memory retrieval activities (tests, quizzes, reminder exercises) are particularly valued. Unlike simple proofreading, the recovery effort lastingly reinforces memory traces and quickly reveals gaps in understanding.

Strengths and limitations of the cognitive model

Cognitivism provides a detailed understanding of learning mechanisms, making it possible to design scientifically optimized training courses. It explains why some methods (like spaced learning) work better than others.

However, this model remains focused on the individual and neglects the social and emotional dimensions of learning. It sees the learner as a rational processor, regardless of interactions with the environment or peers.

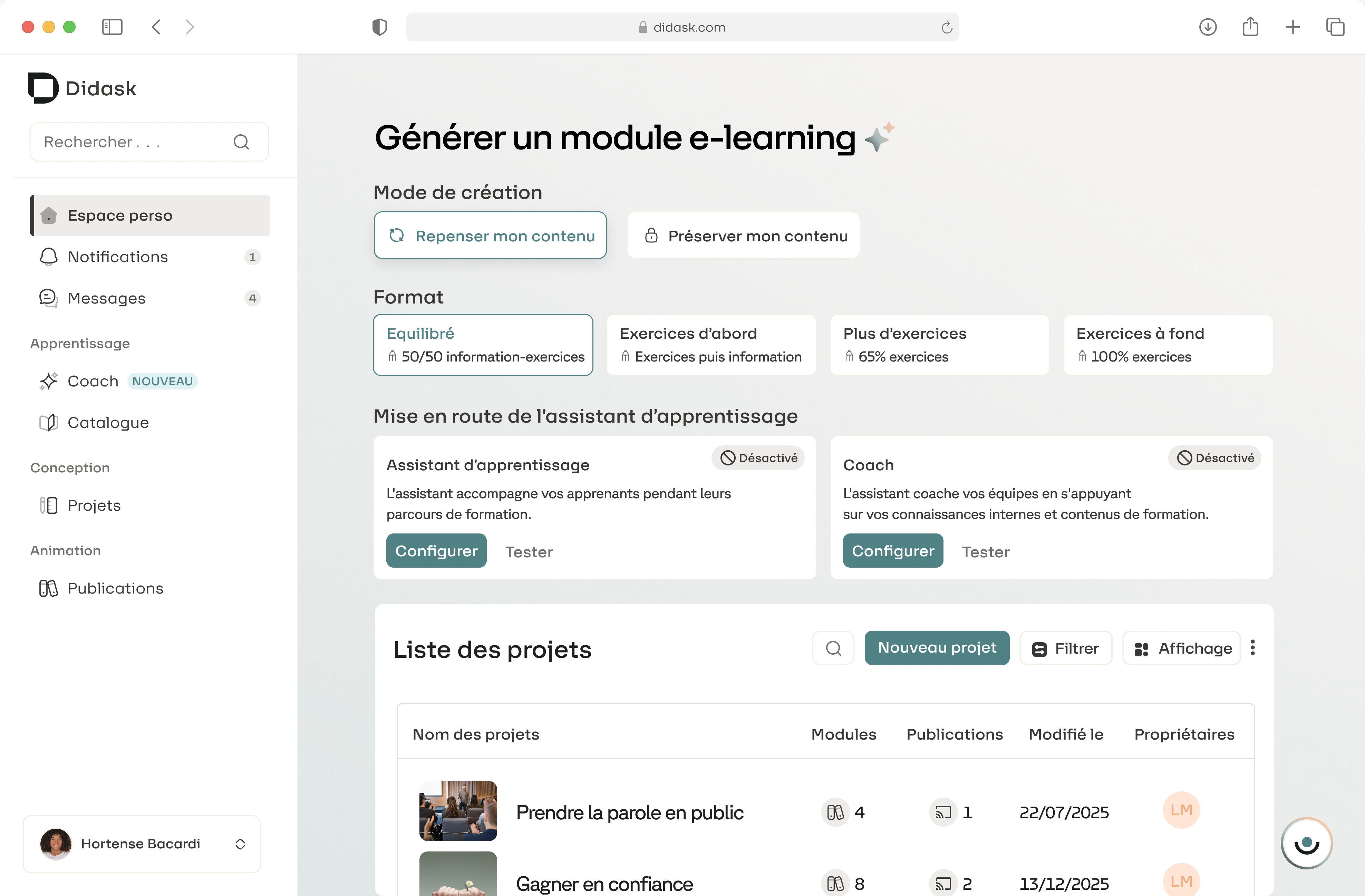

The cognitive journey according to Didask

At Didask, cognitivism is the scientific basis of our pedagogical approach. Our cognitive journey structures learning in successive phases: motivating, deconstructing, remembering, applying cold, then applying hot.

This model integrates principles validated by research: learning by trial and error, immediate feedback, memory retrieval, revision spacing, and desirable difficulty. Educational AI analyzes the level of each learner to automatically adapt the difficulty and personalize the course.

Our embedded instructional facilitator guides designers in creating optimal cognitive learning experiences, even without prior pedagogical expertise. The result: 94% of learners say that their Didask courses have had a positive impact on their daily professional lives.

Constructivism: building your own knowledge

Constructivism overturned the traditional vision of learning in the 1950s. For Jean Piaget, its main theorist, learning does not mean passively receiving information, but actively building one's own understanding of the world.

This theory is based on a revolutionary idea: knowledge does not come from a simple perception of external reality, but from the action of the individual who organizes and structures his experiences.

The mechanisms of cognitive construction according to Piaget

Piaget identifies two fundamental processes in learning: assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation integrates new information into existing mental patterns. Accommodation changes these patterns when the new information does not correspond to the cognitive structures in place.

Equilibration results from the alternation between these two mechanisms. Faced with a situation that contradicts his representations, the learner experiences a cognitive imbalance. This internal conflict pushes him to reorganize his knowledge in order to regain coherence.

Schemas are the building blocks of knowledge. These mental images of reality are constructed through manipulation and aggregation of concepts. A child develops the “dog” pattern by observing different dogs and identifying their common characteristics.

Cognitive conflict: a driver of learning

Constructivism places error at the heart of error. Far from being a failure to be avoided, error reveals the mental representations of the learner and is the starting point of the learning process.

Intentionally creating problem situations is becoming a preferred pedagogical strategy. Faced with a problem that he cannot solve with his current knowledge, the learner must deconstruct his erroneous representations and build new cognitive schemes.

This approach values active experimentation and guided discovery. Instead of conveying the “right answer” directly, the trainer creates rich learning environments where the learner can explore, test hypotheses, and draw their own conclusions.

Vocational training applications

In the corporate context, constructivism inspires active pedagogies such as Learning by doing. Employees learn by manipulating real data, solving authentic use cases, and experimenting in secure environments.

Simulations and Serious Games make full use of these principles. The learner builds his understanding by making decisions, observing their consequences and gradually adjusting his strategies. Mistakes become a learning opportunity rather than a punishment.

Individualized support makes perfect sense from this perspective. The trainer observes the mental representations of each learner, identifies specific cognitive obstacles and proposes situations adapted to cause the necessary imbalances.

Strengths and limitations of the constructivist model

Constructivism recognizes the active and personal dimension of learning. It explains why two people exposed to the same content can develop different understandings depending on their pre-existing cognitive structures.

This approach promotes deep and transferable learning. By building their own knowledge, learners develop authentic understanding that they can mobilize in a variety of contexts.

However, pure constructivism can be time consuming and ineffective for some types of goals. Leaving the learner to discover complex concepts alone risks leading to dead ends or to build erroneous representations.

Piaget's vision also has its limits. Focused on child development, it postulates that learning is only effective if the learner has reached the stage of cognitive development necessary to assimilate it. This conception reduces the role of explicit instruction and places limited emphasis on the social environment in cognitive development.

Didask and constructivist learning

Our platform integrates constructivist principles through learning by trial-error. It is possible to start a module with a situation authentic where the learner must mobilize his current knowledge before receiving explanations.

Personalized feedback precisely identifies erroneous representations and offers appropriate explanations to deconstruct these initial concepts. The learner doesn't just get the correct answer: they understand why their answer was incorrect and how to adjust their reasoning.

Socio-constructivism: learning with and through others

Socio-constructivism enriches Piaget's constructivism by adding a fundamental social dimension. For Lev Vygotsky, its main theorist in the 1930s, learning is fundamentally a social and cultural process.

This theory states that knowledge cannot be built in isolation. The social environment, the peer interactions and cultural mediators (language, tools, symbols) play a decisive role in cognitive development.

Vygotsky's theoretical foundations

Vygotsky introduces the concept of the proximal development zone (ZPD). This zone represents the gap between what a learner can achieve on their own and what they can achieve with the help of a more expert person.

Optimal learning occurs in this intermediate zone. Too easy, the task brings nothing new. Too difficult, it exceeds the abilities of the learner, even with assistance. The role of the trainer or peers is to provide support (Scaffolding) adapted.

Social interactions are not just a complement: they are the very engine of intellectual development. What an individual initially achieves in collaboration with others gradually becomes an internalized capacity that he can mobilize independently.

Socio-cognitive conflict: learning through the confrontation of ideas

Socio-constructivism particularly values socio-cognitive conflict. When several learners confront their different representations on the same object, this discrepancy creates a cognitive imbalance for everyone.

This confrontation pushes learners to explain their reasoning, to justify their positions and to examine alternative perspectives. The process of argumentation and social negotiation leads to a collective reconstruction of knowledge.

The expression “you learn with and through others” perfectly summarizes this approach. Peers are not just stooges: they become cognitive resources that are essential for everyone's development.

Practical business applications

Socio-constructivism scientifically legitimizes collaborative approaches in training. Group work, participatory workshops, and communities of practice build on these principles to promote collective learning.

Peer mentoring effectively utilizes the proximal development zone. A slightly more experienced collaborator can provide more appropriate support than an expert because they better understand the specific difficulties of the beginner.

Collective feedback (debriefings, after-action feedback) creates spaces where participants share their practices, confront their representations and co-construct innovative solutions. These social learning moments often generate more value than formal training.

Advantages and limitations of the model

Socio-constructivism recognizes the richness of social interactions for learning. He explains why 100% remote and isolated training courses often generate less commitment and results than training that integrates collaborative dimensions.

This approach also develops essential transversal skills: communication, argumentation, active listening, management of disagreements. These Soft Skills are becoming more and more crucial in modern organizations.

However, the implementation of socio-constructivism requires expert animation. Badly managed, interactions can lead to superficial exchanges or unproductive conflicts. The trainer must create a safe psychological environment where the confrontation of ideas remains constructive.

Moreover, some fundamental technical apprenticeships first require individual acquisition before actually benefiting from social exchanges. Premature collaboration can sometimes slow learning.

Didask's collaborative approach

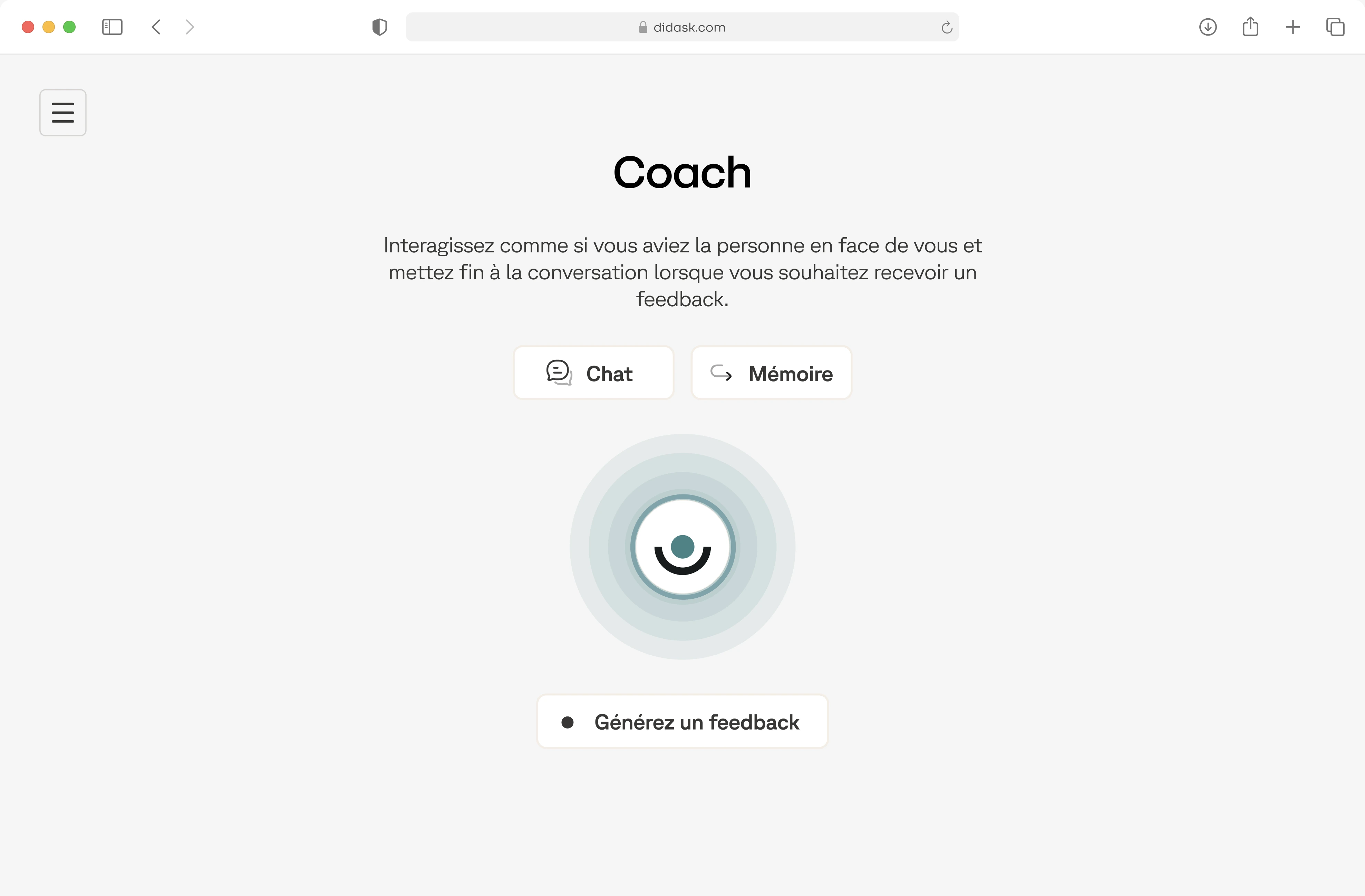

Our AI assistant Didia facilitates social interactions in learning paths. He can propose collaborative scenarios, suggest questions to facilitate constructive debates and identify the optimal moments to create socio-cognitive conflicts.

Connectivism: learning in the digital age

Connectivism represents the most recent attempt to rethink learning in the face of the technological upheavals of the 21st century. Developed by George Siemens and Stephen Downes in the mid-2000s, this model radically questions how we learn in a hyperconnected world.

This theory is based on an observation: classical models (behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism) were developed before the era of the Internet and social networks. They do not sufficiently take into account the profound transformations induced by digital technologies on the ways in which we access, create and share knowledge.

The fundamental principles of connectivism

For Siemens, connectivism integrates principles from chaos theory, network theory, self-organization, and complexity theory. Learning occurs in fuzzy environments composed of changing elements, and is not entirely under the control of the individual.

The central metaphor is based on knots and connections. A node can be a person, information, resource, resource, website, or any entity connected to others. Learning consists in creating and developing networks of connections between these nodes.

Knowledge can now reside outside the individual, in organizations or databases. The challenge is no longer just to have knowledge, but to know where to find it and how to mobilize it at the right time. “Know-where” complements traditional “know-how” and “knowledge-what”.

Eight principles for networked learning

Connectivism is divided into eight operational principles validated by Siemens and Downes. Learning is based on the diversity of opinions and sources of information. Multiplying perspectives enriches understanding.

The ability to acquire new knowledge is becoming more important than the stock of knowledge already possessed. In a rapidly changing world, the obsolescence of knowledge is accelerating. Knowing how to learn continuously takes precedence over what you already know.

Connections that allow us to learn more are more important than the current state of our knowledge. Developing a professional network, identifying relevant experts and creating links with reliable sources of information are strategic skills.

Decision-making itself is becoming a learning process. Distinguishing important information from unimportant information, evaluating the reliability of sources, and adapting to constant changes in the information context require lifelong learning.

Applications in vocational training

Connectivism legitimizes the massive use of technologies for learning: professional social networks, online communities, collaborative platforms, content curation and MOOCs. These tools are no longer simple supports: they are becoming the very field of learning.

Networked learning promotes the development of personal learning environments (Personal Learning Environment). Each learner builds their own ecosystem of resources, tools, and contacts that evolves continuously according to their needs.

Businesses that adopt this approach encourage their employees to develop their presence on professional networks, to participate in virtual communities of practice, and to share their knowledge. Informal learning via networks complements formal arrangements.

Scientific debates and criticisms

Connectivism is the subject of controversy in the scientific community. Some researchers like Plon Verhagen challenge its status as a learning theory. For them, it is more of a pedagogical approach that describes how to organize learning without explaining how the individual actually learns.

Other critics point out that connectivism recycles ideas that are already present in other currents (communities of practice, distributed cognition, collective intelligence) without bringing a real theoretical break.

Stephen Downes himself insists on a fundamental distinction: in connectivism, “building knowledge” makes no sense. Connections are formed naturally through association; they are not “built” intentionally. This position is radically opposed to constructivism.

Finally, the evaluation of learning is a problem from a connectivist perspective. How do you measure the quality of a knowledge network? How do you assess the ability to access information rather than to have it? Traditional methods (tests, multiple choice questions) are becoming obsolete.

Artificial intelligence according to Didask

Our AI assistant Didia embodies a connectivist approach to professional learning. It supports employees both during formal training and during their daily activities, creating a continuum between learning and working.

Didia recommends relevant courses according to the profile and needs of each learner, offers individualized support adapted to the context and allows training in a real situation. This AI assistant also facilitates the retrieval of information when needed and anchors best practices over time.

This connectivist approach integrates naturally with existing business tools. Educational AI creates bridges between different sources of knowledge (training, documentation, internal experts) and makes them accessible at the right time.

How do you choose the right model for your training?

Faced with this diversity of learning models, a question naturally arises: which one should you choose for your corporate training? Cognitive science research provides a nuanced answer: there is no universally superior model.

Educational effectiveness always depends on three factors: the intended learning objectives, the target audience, and the context of implementation. The same model may be optimal for some situations and counterproductive for others.

Adapting the model to the educational objectives

To develop automation and routine procedures, behaviorism remains particularly effective. Repetitive technical actions, security protocols or administrative procedures benefit from this structured approach through positive reinforcement.

Rather, the goals of conceptual understanding require cognitivist or constructivist approaches. Understanding a complex phenomenon, mastering reasoning or developing expertise requires the construction of elaborate mental diagrams.

Collaborative and communication skills emerge naturally from socio-constructivist practices. Facilitating a meeting, managing a conflict or negotiating is better learned in social interaction than in isolation.

Finally, the skills of monitoring, curation and autonomous learning are part of a connectivist approach. Knowing how to navigate information, evaluate sources and build a learning network is learned by practicing these activities in authentic digital environments.

The integrative approach: research recommendation

Contemporary researchers are converging on a pragmatic conclusion: maximum effectiveness comes from an intelligent combination of different models according to the learning phases and the objectives targeted.

Blended learning is a perfect example of this integrative approach. Training can start with individual cognitive sequences to build the fundamentals, continue with socio-constructivist workshops to confront practices and be continuously enriched via connectivist resources.

The personalization of learning also benefits from this plurality. Adaptive systems mobilize behaviorist techniques to automate certain learning, cognitive strategies to optimize the presentation of information, and connectivist tools to recommend relevant resources.

Didask's approach: a scientific synthesis

At Didask, we don't believe in the supremacy of a single learning model. Our approach is based on a pragmatic synthesis of the most solid discoveries in cognitive science research, integrating the complementary contributions of each theory.

This philosophy is embodied in the concept of the cognitive journey, developed after several years of R&D in collaboration with researchers in cognitive psychology. This model reconciles the cognitive approach and the development of complex skills.

The cognitive journey: an integrative model

Our cognitive journey structures learning into five progressive phases corresponding to the cognitive challenges of the learner. The motivation phase activates prior knowledge and creates the need to learn (constructivist dimension).

The deconstruction phase confronts the learner with his erroneous representations through authentic situations. This controlled challenge generates the cognitive conflict necessary for the transformation of mental patterns (constructivist and cognitivist approach).

Memorization uses the principles of spacing and retrieval validated by cognitive research. Essential information is reactivated at optimal intervals to permanently anchor knowledge in long-term memory (scientific behaviorism).

Cold application makes it possible to mobilize new skills in guided and secure contexts. The learner understands how he could put his learning into practice (applied cognitivism).

Finally, the hot application confronts the learner with complex real situations where he must mobilize his skills without error. This phase develops the expertise and the automation necessary for professional performance (behaviorism and constructivism combined).

Educational AI at the service of efficiency

Our Didia AI assistant automatically customizes the courses according to the level and needs of each learner. This continuous adaptation integrates a connectivist dimension: AI identifies relevant resources, recommends complementary paths and facilitates connections between employees.

The adaptive learning analyzes the responses of each learner to precisely identify their shortcomings and adapt the difficulty in real time. This approach ensures that everyone progresses in their proximal zone of development (socio-constructivist concept applied by technology).

Personalized feedback isn't just about whether the answer is right or wrong. They explain the expected reasoning, identify the origin of the error and offer explanations adapted to the specific representations of the learner (in-depth cognitivism).

Measurable and scientifically validated results

The Didask approach generates a quantifiable impact on skills. 94% of learners say that their Didask paths have had a positive effect on their professional daily lives. This performance is explained by the rigorous integration of validated scientific principles.

Our methodology is based on the most robust meta-analyses in cognitive psychology and on reference works (Clark & Mayer, Roediger, Kirschner, Dehaene, Hattie). Each feature of the platform corresponds to a specific scientific recommendation.

The embedded educational facilitator democratizes access to this expertise. Designers with no pedagogical background can create scientifically optimized courses thanks to intelligent guidance that suggests formats and activities adapted to the desired objectives.

A complete solution for all organizations

Didask adapts to all organizational contexts: large companies, SMEs, training organizations and associations. Our platform can be deployed as LMS complete or integrate with existing solutions to enhance their educational effectiveness.

More than a hundred organizations already trust Didask: ENGIE, BNP, Canal+, L'Oréal, Orange, Suez, SIG. These customers share a common ambition: to go beyond the simple dissemination of information to generate a real transformation of skills.

Conclusion

Learning models are not simple abstract theories reserved for researchers. They are concrete tools for designing training courses that really work, based on our scientific understanding of how the brain works.

From behaviorism to connectivism, each model provides complementary insight into the mechanisms for acquiring skills. Behaviorism remains effective in creating automations. Cognitivism optimizes information processing. Constructivism promotes deep understanding. Socio-constructivism exploits the richness of social interactions. Connectivism meets the challenges of digital learning.

Contemporary research converges on a pragmatic conclusion: pedagogical excellence is born from an intelligent combination of these different approaches, adapted to the specific objectives and context of each training course. The challenge is no longer to choose the “right” model, but to orchestrate them harmoniously.

At Didask, this scientific synthesis is realized through the cognitive journey and educational AI. Our ambition: to make the effectiveness of personalized tutoring accessible to all organizations at large scale.

.png)