Your employees complete their training courses with 100% success rates. However, on the ground, nothing is changing. The problem is not the motivation of your learners. It's their level of commitment cognitive during training.

What is cognitive engagement?

Cognitive engagement measures the intensity of mental effort made by the learner during learning. This concept, which is central to Stanislas Dehaene's work on the pillars of learning, is radically different from behavioral or emotional engagement.

A learner can be perfectly behaviorally engaged. He clicks, he advances through the modules, he finishes his courses. He may even be happy with the experience. But if his brain is operating on autopilot, learning just doesn't happen.

The researcher Michelene Chi formalized this distinction with the ICAP model. This theoretical framework prioritizes four levels of cognitive engagement, from the most superficial to the most profound. At the Passive level, the learner receives information passively without actively processing it. At the Active level, it manipulates information in a basic way. At the constructive level, it generates new ideas from the content. Finally, at the Interactive level, he co-builds his understanding in dialogue with others or with a system.

This hierarchy reveals an unsettling truth. The majority of digital training keeps learners engaged on the surface. They read, they look, they click on the right answer. Their brains recognize familiar patterns without ever really thinking. The illusion of mastery sets in, reinforced by perfect quiz scores. But transferring this knowledge into a real situation is becoming impossible.

Checklist: does your training promote in-depth cognitive engagement?

Evaluate the level of cognitive engagement of your training courses using these criteria:

Do your exercises require active production?

The learner must formulate, write and justify his answers. Multiple choice MCQs where the correct answer is obvious are not enough. The brain needs to actively generate a response, not simply recognize it among options.

Does the difficulty level create a desirable difficulty?

Your exercises should be located in the proximal development zone. Not too simple to the point that the learner answers without thinking, nor too complex at the risk of causing abandonment. The right level requires authentic cognitive effort while remaining achievable.

Do the application contexts vary enough?

Offering the same type of exercise with slightly different data does not stimulate in-depth thinking. Vary situations, alternate contexts, multiply practical cases. This diversity forces the brain to really understand the concept rather than memorize a pattern.

Does feedback encourage analysis and correction?

A simple “Correct” or “Incorrect” does not stimulate any cognitive processes. Feedback should push the learner to analyze their error, understand why their response was inappropriate, and adjust their reasoning. It is in this metacognitive reflection that learning is consolidated.

Does the learner have to actively mobilize their knowledge?

Memory retrieval activities significantly increase retention. Instead of passively rereading the content, the learner must look for the information in their memory. This active search, even if it generates initial errors, strengthens neural connections much more effectively than passive revision.

Are the scenarios authentic and complex?

Simplified and decontextualized scenarios do not engage cognitively. Learners must face situations that are close to their professional reality, with their ambiguities and constraints. This realistic complexity requires the brain to activate several cognitive strategies simultaneously.

Are you really measuring cognitive engagement?

The time spent and the completion rate reveal nothing about the intensity of mental effort. Instead, analyze engagement indicators such as the error rate during the exercises, the time spent thinking before responding, the quality of productions, or the number of attempts. These metrics reveal whether your learners are really thinking or navigating on autopilot.

Do you cultivate a growth mindset in your learners?

Carol Dweck has demonstrated the importance of the state of mind in the face of effort. If your learners perceive the difficulty as a personal failure, they will avoid deep cognitive engagement. Your training should value effort, normalize error as an integral part of the learning process, and present challenges as opportunities for development.

How to integrate cognitive engagement into your training?

Turning passive training into a cognitively engaging learning experience requires a fundamental rethinking of your teaching approach. Educational modalities should be selected based on the cognitive processes they activate, not on their aesthetic appeal.

Start by identifying key moments where cognitive engagement needs to be maximum. During the phase of deconstructing erroneous ideas, propose situations that put the learner in front of his initial conceptions. Let him hypothesize, make a mistake, and then analyze why his answer was inadequate. This cognitive conflict, while uncomfortable, is an extremely powerful learning tool.

During the application phase, multiply the practical cases by systematically varying the contexts. This intertwined learning method, validated by numerous studies in cognitive science, forces the brain to discriminate between situations and to adjust its strategies. The learner can no longer apply a procedure mechanically. He must analyze each situation, identify its specificities, and adapt his approach.

Memory recovery exercises should punctuate the course regularly. These active development and generation activities create robust memory connections. The effort to recover, even if it temporarily generates more errors than simple proofreading, produces significantly more lasting learning.

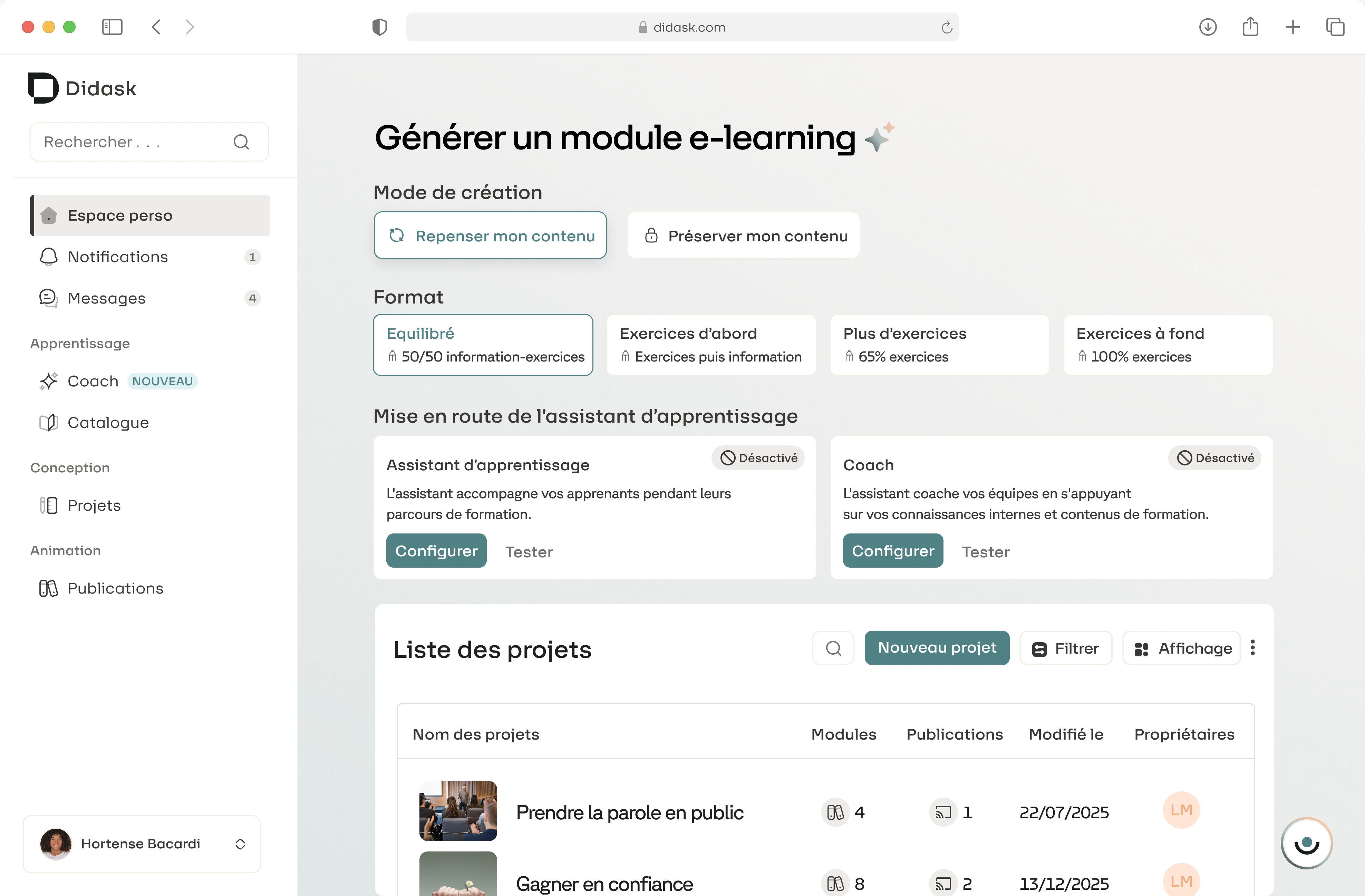

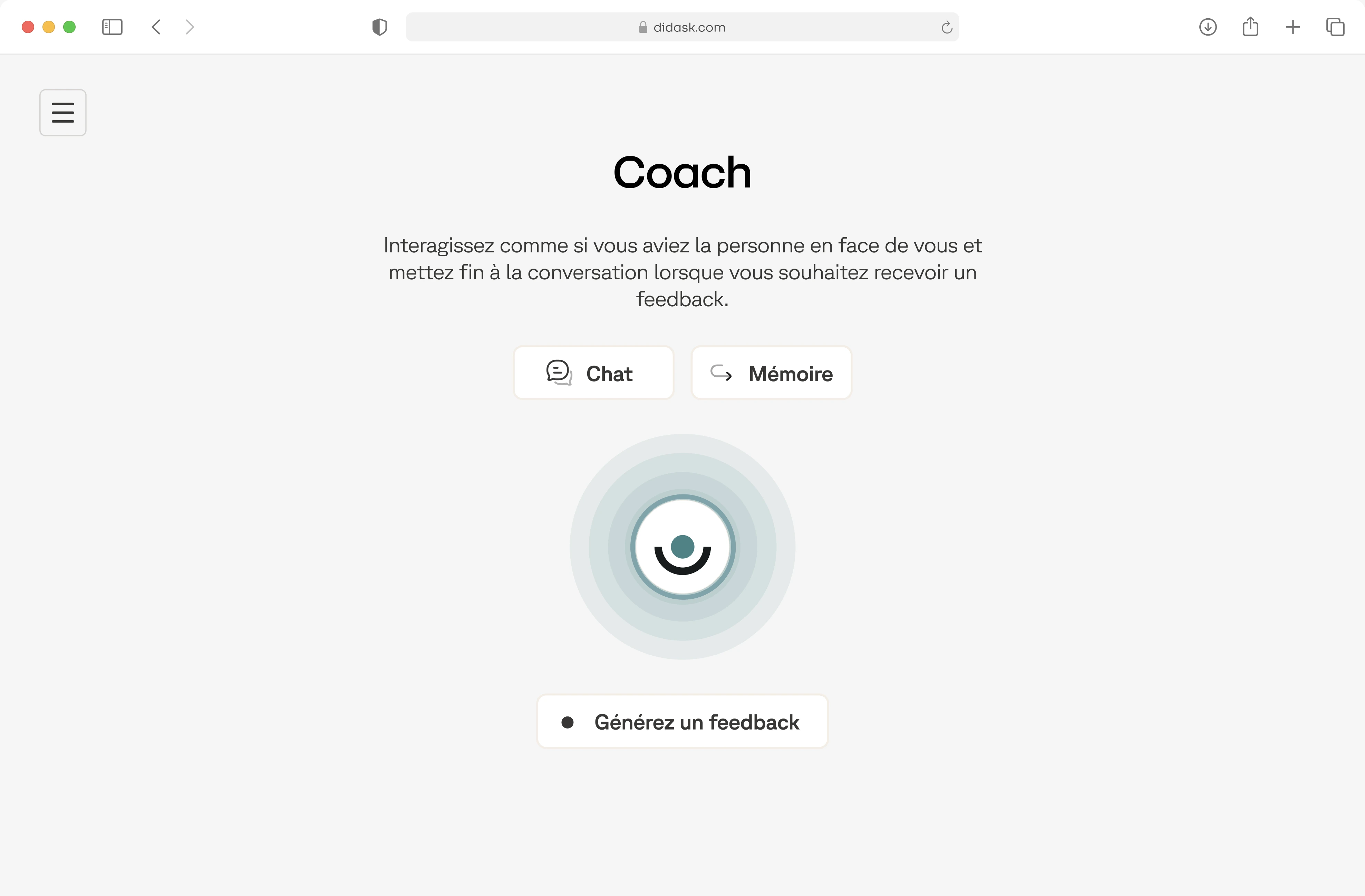

Technology can serve this purpose of cognitive engagement. Didask's AI assistant, for example, makes it possible to automatically generate Situations personalized adapted to the professional context of each learner. This personalization increases perceived relevance and promotes deeper cognitive engagement than with generic exercises.

Measurement tools must also evolve. An effective educational dashboard does more than just show completion rates. It reveals the moments when learners are making authentic cognitive effort. The success rate in the exercises, the distribution of attempts, and the average thinking time become essential indicators for adjusting the difficulty and maintaining engagement in the optimal zone.

Cognitive engagement at the heart of pedagogical effectiveness

Cognitive engagement is not a pedagogical luxury reserved for excellent training. This is the critical factor that determines whether your training investment generates a real increase in skills or simply completion certificates.

Organizations that understand this distinction are radically changing their approach. They stop measuring engagement by the number of connections to the platform. They assess the intensity of cognitive effort made during learning. They accept that lower initial success rates can signal deeper engagement, and therefore longer lasting learning.

This evolution requires a paradigm shift. Designers must abandon the goal of “making training enjoyable” in favor of “creating an optimal cognitive challenge.” Trainers should value productive difficulty rather than celebrate successes that are too easy. And learners need to understand that cognitive discomfort is not a system bug, it's a signal that their brain is learning.

Your next course should elicit this reaction from your learners: “I really had to think, but now I get it.” Not: “It was quick and easy.”

.png)