The essential questions to ask yourself to properly assess the acquisition of a skill

You are looking to train your new employees in customer relations. You know the drill: The learners will follow a day of training, maybe an e-learning... and then? How can you be sure that there will be something left over from their apprenticeship this time around? You naturally think of certification training: yes, but for what certification criteria? How to verify the real acquisition of the targeted skills?

One might think that the challenge boils down to the design of a final test or exam that would make it possible to check the boxes of what was seen during the training. In truth, the challenge is wider and involves asking 3 main questions: What to test? How to test? How many times to test?

1. What skill to test: a specific objective is an evaluable objective

Let's say you want your employees to follow an online diploma course on a Soft Skill like “digital culture.” If you are given the mission to imagine a final diploma exam, you probably won't know where to start. It's normal! With a vague objective like this, you will have a hard time designing a relevant evaluation.

Most of the work must be done beforehand, in the definition of educational objectives. The more finely divided your goals are; the more they reflect a clear change in state, the easier it will be for you to test them. (this is the subject of our article on optimization of training objectives). Thus, you could break down your digital culture journey into micro-skills associated with a well-identified progression: for each skill, contrast the final state of the learner with his initial state.

Let's take the example of the skill “managing your digital identity”. Someone who masters this skill will know how to manage their online privacy settings, avoid posts that could harm them, or even react to a negative comment. Once you get there, the skill test exercise is almost self-written! By properly identifying your educational objectives, you are therefore doing more than half of the work required for a successful assessment of a competency acquisition.

2. How to test: as close as possible to real conditions

You still have to conceive tests that faithfully meet your goals. A common mistake in this area is to expect learners who have been evaluated mainly on theory to come out of a course fully operational. However, we do not give a license to all those who pass the traffic code: we wait to see what they do with the wheel in their hands! It's the same for any training. Training bank employees in new regulations on money laundering is not simply evaluating them on their knowledge of the new procedures to follow, it is also putting them in front of customer files that they will have to accept or not accept as part of these procedures.

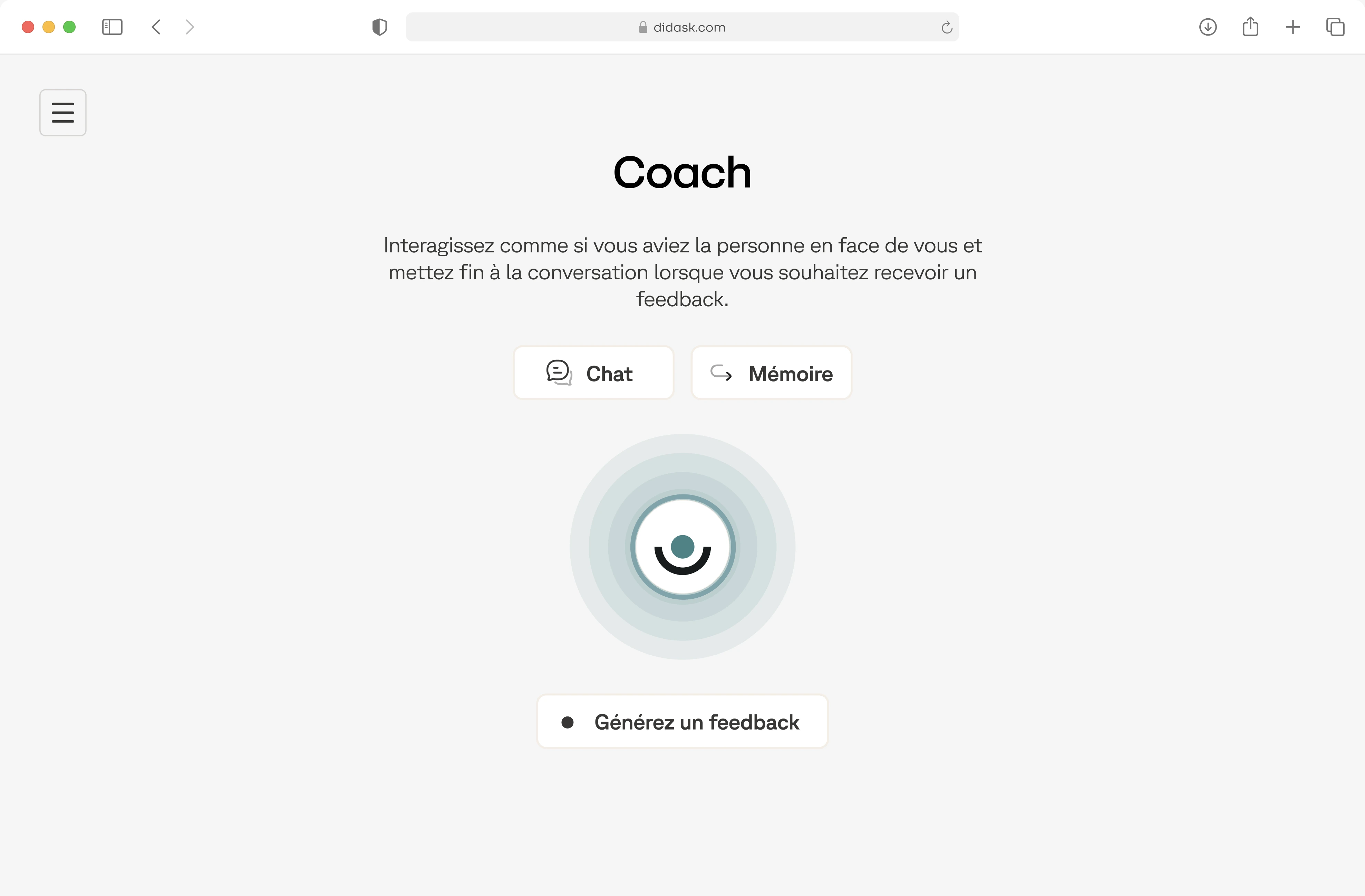

In the same logic, the assessment tests must offer a difficulty comparable to that which the learners will encounter in a real situation (see our article on desirable difficulties). The astronaut is tested in zero gravity and not in the atmosphere: why should it be any different from your learners? Take the case of a Training about safety. Your interns are going on a mission near a dangerous border. To assess them, you can interview them orally: “You arrive at a checkpoint, a militiaman asks you to open the trunk of your vehicle to check that you are not transporting anything illegal. What are you doing? ”. Learners can answer correctly in the comfort of a heated room, but are you sure they'll react the right way when they're scared to death when faced with a heavily armed man? A simulation would therefore be preferable here to capture this additional difficulty that is fear. Of course, a perfect simulation is rarely possible, but in any case you have to ask yourself What would be the best approach to a real situation taking into account your resources. The method of identifying “relevant errors” that we have integrated into our solution at Didask is a good way to do that.

What you need to remember here is that the change you want for your learner is a change in work, at school, on a daily basis: it does not end at 6 p.m. on the day of the training. You should carefully avoid anything that, in your evaluation, could create a bubble separating learning from “real life”.

3. When to test: towards lifelong assessment

Precisely for this reason, the question of The evaluation, in the singular, by that Assessments, in the plural. The final exam should give way to Lifelong assessment, in all serenity.

Most of the time, a course or training course is built as follows: one or more knowledge transmission sessions, then a final exam (a kind of last judgment that would make it possible to separate the good from the bad) at the end of which the learners are released into nature. This model, inherited in part from the school, could be improved in two ways.

First by getting into the habit of test learners regularly before the exam. If you want to train in the HTML/CSS computer language, rather than focusing everything on a single final project at the end of the training (create a complete web page), why not propose micro-projects to be carried out at each stage of the training (create a menu, create a table...)?

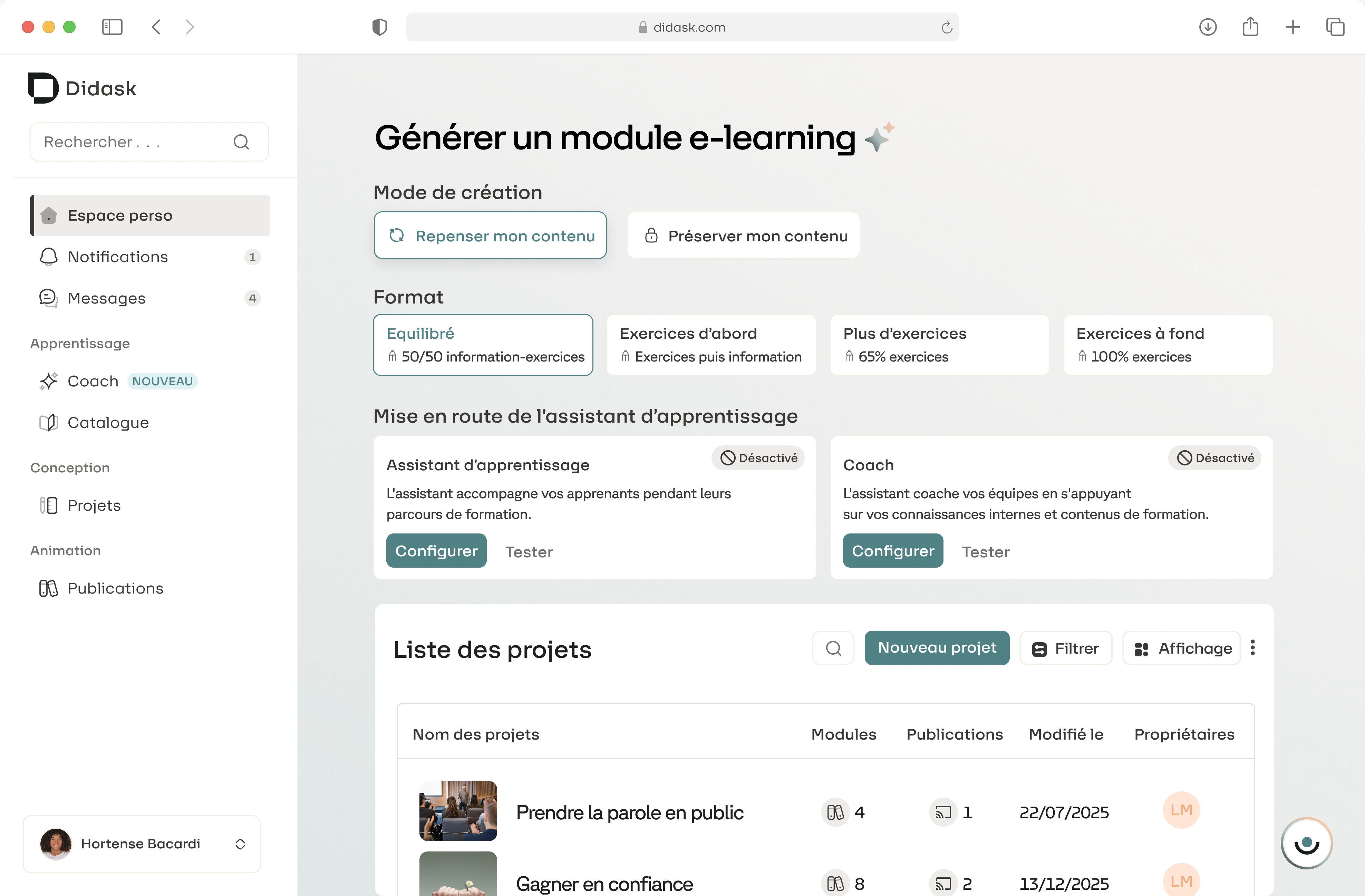

Then, by encouraging them to continue test themselves after the exam : you could thus encourage your learners to take on small challenges related to their learning from time to time to check that they continue to progress on a daily basis. Thus, as part of a training course on the quality of life at work, your learners could make the commitment to create a daily schedule with real breathing ranges, then check to what extent they respected this schedule. In the Didask eLearning Solution, for this purpose, we have integrated micro-challenges, which are offered to learners at the end of the modules.

This constant (self) evaluation produces 3 positive effects:

- First of all, it allows you to have corrective feedback : if you did not understand the first lesson on Newton's laws of motion, it's better to know it right away than to discover it at the time of the exam, when you have to predict a series of complex trajectories (see our articles on Illusion of mastery and on the Testing Effect).

- secondly, the multiplicity of evaluations makes it possible to diversifying learning contexts. The skill of speaking in public, for example, is not exercised in the same way depending on whether one speaks to a small group or to a large group, or whether one speaks with or without notes.

- Thirdly, Evaluating more often makes it possible to de-dramatize the relationship with error. (read on this subject the article on learning by trial and error: unleash the potential of feedback). Once trivialized, the evaluation ceases to be a definitive judgment on the person, to become an estimate at the moment T of your progress in a continuous learning process.

A striking objective, exercises that are as close as possible to reality, a trivialized evaluation : all elements that will allow you to ensure that your learners can attest to the skills they have acquired, not only through a diploma or certification, but also and above all in their positions and in their lives every day.

.png)