Recently, a MIT Media Lab study has agitated social networks. According to viral summaries that have been circulating, using ChatGPT while learning would make us lazy... and create cognitive debt.

Is the tool that simplifies our daily lives hampering our mental abilities? Not so fast.

The study raises a real question: are LLMs learning accelerators or crutches that weaken our cognitive abilities?

But on closer inspection, its results show above all that when a task is delegated to an external tool, cognitive performance decreases — which is not in itself a new discovery, nor proof of a lasting impoverishment of our abilities.

Above all, this does not mean that the use of LLMs creates “cognitive debt”. We will even see that they can, in some cases, reinforce learning.

To fully understand what this study is saying (and not saying), you still need to take a close look at what it is actually testing.

Focus on the MIT Media Lab study

In this study, researchers assessed the impact of using ChatGPT on cognitive engagement during a writing task. To do this, they recruited 54 participants divided into three groups: a “without tools” group, a group using traditional search engines, and a group with access to ChatGPT. Each participant went to the laboratory three times to write an essay, each time on a subject chosen from three proposals (for example: happiness, loyalty, etc.).

During each session, four variables were measured: brain activity (via EEG), the quality of the texts produced, declarative memory (ability to remember what had been written) and the feeling of intellectual property regarding the trial.

The results show a clear pattern: although texts written with the help of ChatGPT are considered to be of higher quality, participants in this group have significantly reduced brain activity, a poorer memory of their production and a lower sense of ownership compared to the group without tools. In other words, the tool seems to induce cognitive disengagement.

To go deeper, the authors conducted a follow-up session with 18 of the initial participants. This time, the conditions were reversed: those who used ChatGPT had to write without help, and vice versa. The results of this “transfer” session are particularly enlightening. Participants switching from ChatGPT to tool-free regain a level of brain activity and memory similar to those who have never used AI. Conversely, those moving from toolless to ChatGPT see their cognitive engagement drop rapidly.

This point is crucial: the observed effect is not irreversible. The use of ChatGPT does not seem to induce lasting damage or “cognitive debt” preventing future engagement, but rather a temporary state of lower cognitive mobilization, reversible as soon as we regain control of the task.

This nuance is worth noting, especially as several reactions to the paper exaggerated its implications by claiming that ChatGPT would “damage our brains.” However, the data does not support this thesis. Rather, they illustrate an intuitive phenomenon: when you delegate a task to an intelligent tool, you naturally provide less cognitive effort. It's nothing new. The same effect is observed when using a GPS for orientation : some cognitive resources are less solicited, and memorization is affected.

That said, there are several limitations that need to be taken into account. First of all, the study is a preprint, i.e. it has not yet been peer-reviewed, an essential step in validating the methodological robustness and interpretation of the results. Second, the sample size is relatively modest (less than 20 participants per group), which is rarely ideal for EEG measurements, which are known for their high inter-individual variability. Finally, the results relate only to one specific task: writing an essay.

So does it have to be concluded that using LLMs like ChatGPT is detrimental to learning? Not necessarily.

On the contrary, other studies show that LLMs can promote future learning, especially when they are used as feedback or clarification tools, and not as a substitute for the task itself.

LLMs that improve learning

The experiment conducted by Lira et al. (2025) on the writing of cover letters provides interesting additional insight. The researchers conducted two experiments, with the random distribution of participants. In the first, they were assigned to writing training, with or without AI assistance. All of them then took an unaided essay test the following day.

Contrary to the majority predictions, participants who practiced with AI performed better on this final test. Even more surprising: they put in less effort during the training phase — as evidenced by the time spent, the number of keystrokes, and their subjective evaluations — while achieving better results.

The second experiment reveals a particularly instructive mechanism: participants who simply observed examples generated by AI (without being able to modify them) obtained results comparable to those who actively used the tool. This finding suggests that exposure to high-quality productions can generate implicit learning, enriching learners' mental models even without direct interaction.

In other words, AI is not always a substitute for mental effort or effective learning. In some contexts, it can even reinforce them. These results echo those of Bastani et al. (2024), which show that the impact of GPT depends strongly on the uses we make of it, as well as on the cognitive and metacognitive contributions that it allows to activate.

In this study conducted with nearly 1,000 Turkish high school students studying mathematics, researchers compared the impact of different ways in which GPT-4 was used on learning. Three groups were formed: a control group with classical resources (manual and notes), a “GPT” group with a standard ChatGPT interface, and a “GPT Tutor” group with a version specifically designed according to pedagogical principles.

The experiment lasted one semester, with assisted practice sessions followed by final evaluations without assistance. The researchers measured both immediate progress and final performance.

The results reveal a striking contrast: the “GPT” group saw their performance increase by 48% during the assisted sessions, but showed a decrease of 17% during the final exams compared to the control group. In contrast, the “GPT Tutor” group not only improved their performance by 127% during the training sessions, but maintained a level equivalent to the control group during the final evaluations.

This difference is explained by the radically different design of the “GPT Tutor” system: educational prompts of more than 500 contextualized words, guidance by progressive clues rather than the direct provision of answers, integration with the educational objectives set by the teachers... All these safeguards that prevent the passive use of AI as a simple “response machine” and promote the activation of personal reasoning.

The Didask approach: four pillars to avoid the technological crutch effect

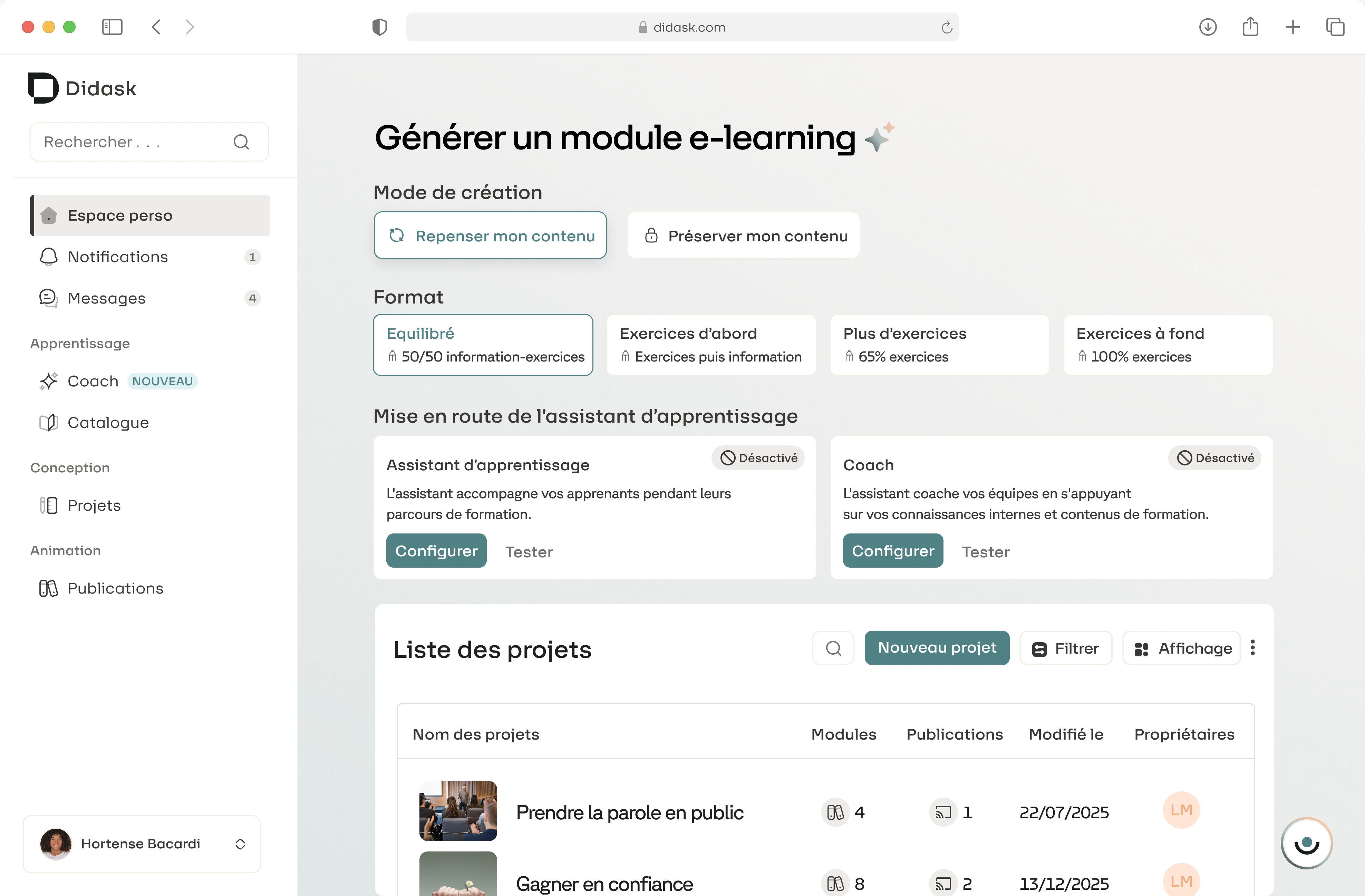

Faced with the excesses identified by research, Didask has developed an AI integration approach focused on sustainable learning, rather than on immediate performance. This strategy is based on four pillars designed to make AI a real educational catalyst.

1. Adaptive journeys: in-depth cognitive personalization

At Didask, the Adaptive learning is not limited to adapting the content. In less than 5 minutes, the system generates positioning tests that identify the cognitive challenges specific to each learner.

Let's take the example of a sales training course in five modules: understanding the products, engaging the customer, unfolding the pitch, managing objections, concluding the sale. Claire, already familiar with the products, will quickly validate module A and will be offered the B-C-D-E course directly. Thomas, an experienced salesperson but not at ease with the hook-up phase, will follow an A-C-D course adapted to his specific needs.

This granularity makes it possible to reduce cognitive overload while respecting what has been learned. The algorithm avoids superfluous educational interventions to concentrate the effort where it is really needed. An approach aligned with the principles derived from research: AI must enhance efficiency without short-circuiting the essential cognitive effort.

2. Immediate and contextualized feedback: learning by mistake, without dependency

Educational AI Didask automatically generates, for each response from a learner, explanatory, benevolent and contextualized feedback. Unlike ready-made answers that induce a form of dependency — as Bastani's work has shown — these returns aim to explain the reasoning, and to reinforce the anchoring of the key message.

Mistakes are treated as learning opportunities. The exercises are designed to naturally bring out common mistakes in realistic dilemmas. Each option is simple, plausible, and the feedback provides real informational value. The learner understands what is right, why it is right, and how to avoid mistakes in the future.

A logic directly in line with the Lira study: exposure to quality examples, accompanied by structuring explanations, enriches mental patterns without creating dependence.

3. Situations rooted in the real professional world

One of the strong specificities of Didask is its ability to generate authentic situations, directly from the professional daily life of learners. Educational AI creates concrete scenarios in one click, with plausible choices that reflect the realities on the ground.

The formats are varied: from the simple “what would you do?” ” to more complex categorization sequences, procedures, or multiparameter simulations. The objective: to enable the learner to make the right decisions in contexts similar to those he will encounter in the field.

This contextualization makes it possible to avoid a pitfall that is often pointed out in research: the generality of LLMs, which limits their transferability. By anchoring each situation in business specificities, Didask maintains commitment and ensures pedagogical relevance.

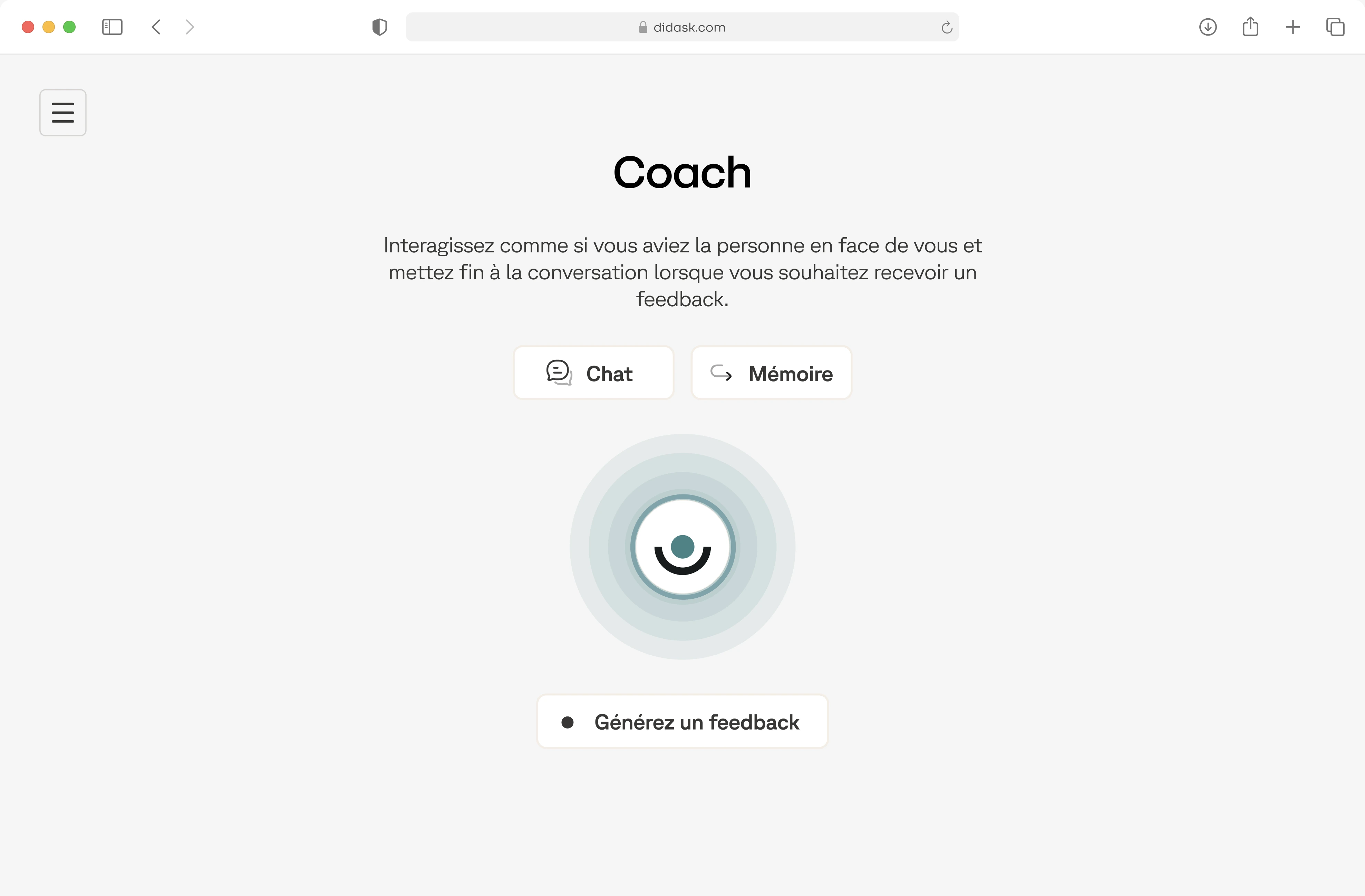

4. Didia: an omnipresent learning assistant, with safeguards

Didia embodies a new generation of teaching assistants: more than a chatbot, it supports employees in their learning, formal and informal.

During the training, Didia helps learners to better understand the content: reformulations, examples, links between concepts... just like a human tutor would.

Apart from the modules, Didia answers daily business questions. A manager facing his first team conflict can describe his situation and obtain contextualized support, based on the company's knowledge base. The AI offers targeted practical cases and suggests complementary modules to deepen.

This permanent support gives rise to a true continuous learning ecosystem, much richer than a simple chatbot, and which goes well beyond the framework of one-off training. Didia integrates the safeguards recognized by the scientific literature as essential: fine contextualization, progressive guidance, structured progression. These are all levers that promote learners' autonomy, without slipping into dependence on the tool.

Conclusion

Integrating LLMs into apprenticeships is neither intrinsically beneficial, nor fundamentally problematic. Empirical data shows that their impact depends above all on the quality of their pedagogical integration.

Between tech-savvy solutionism and conservative rejection, a middle path is needed: that of reasoned cognitive augmentation, where AI amplifies human abilities without replacing them.

At Didask, it is this trajectory that guides the development of our devices: learning environments where LLMs become real cognitive partners, rather than intellectual crutches. This implies an intentional design of interactions, preserved human support, and constant attention to the balance between immediate effectiveness and sustainable development of skills.

It is under this condition that AI will be able to contribute to a truly virtuous educational transformation.

.png)